Recent book:

Nazis, Islamic Antisemitism and the Middle East

Joschka Fischer, Yasser Arafat and the Road Map Peace Plan

December 2003

This essay, based mainly on German sources, looks into the history of the diplomacy of the international Road Map. I completed the German version in September 2003 after the Palestinian prime minister, Mahmud Abbas, resigned and the Road Map Peace Initiative was brought to a standstill.

Today, more than ever, we witness renewed attempts to forge a peace agreement: the Geneva accord, the Ayalon/Nusseiba-initiative and others. They are all giving expression to a desire for peace which is welcome.

Rarely, however, do we find a genuine interest in addressing the matter why to date each peace plan, including the Road Map, has failed. Yet the questions submitted yesterday by the renowned scholar on Islam, Bernard Lewis, in Berlin, raises valid concerns:

“Do the Palestinians really want peace? Are they interested in solving the problem as to where the future border (of a two-state solution) will be or are they primarily interested in the extermination of the Jewish Nation? Bernard Lewis, the doyen of Islam studies within the English speaking world, directed these questions at the German Foreign Minister with a note of scepticism. Lewis sees several of the European countries in the tradition of the Third Reich and that of the Soviet Union. As in that period ‘several European governments allow themselves to be taken in by the Arabs in their fight against the Jews and the USA.’ “[i] This assessment might be too pessimistic so let us have a closer look.

Matthias Küntzel, Hamburg, December 8, 2003.

On April 30, 2003, the “Road Map Peace Plan” was presented to Ariel Sharon and Mahmud Abbas, the newly elected Palestinian prime minister. Shortly thereafter, Joschka Fischer, Germany’s foreign minister, bragged: “Look at what we Europeans have achieved in the Middle East! This peace plan … was engineered by Europeans. The other members of the Quartet then adopted it and developed it further. On the whole, however, it is European.”[ii]

We certainly have to take such boasting with a grain of salt. It’s true that the Road Map for “home consumption is called the “US” Road Map in America. It is, however, a Quartet Road Map with the USA being one of four members including the European Union (EU), the UN and Russia.

Unfortunately, the melody of this Quartet has never been harmonious. US policy has been at odds with the EU in particular. And in retrospect we realize that the failure of this latest peace plan was, to some extent, preordained by those very transatlantic quarrels. But the story of this failure also reveals the scope of disagreement within the Western camp as far as Islamist terrorism is concerned.

Work on the International Road Map started in April 2002, after Hamas killed 29 people at a Passover celebration in the Israeli city of Netanya. Then, President Bush intervened forcefully by issuing a statement on April 4, 2002. On April 9, Joschka Fischer presented his “Conceptual Paper for Peace in the Middle East”. One day later, the “Middle East Quartet” was created in Madrid. Joschka Fischer’s “Conceptual Paper”, however, had nearly nothing in common with George W. Bush’s statement.

The latter’s words were mainly directed against Hamas: “There is no way to make peace with those whose only goal is death.” President Bush acknowledged Israel’s right to defend herself against terror, and he urged Palestinians and the Arab governments to put a halt to all “terrorist activities” of the Al Aqsa Brigades, Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad and Hamas. He called on them to “disrupt terrorist financing, to stop inciting violence by glorifying terror in state-owned media”, and to stop talking about martyrs: “They’re not martyrs, they’re murderers” he said.[iii]

On the other hand, Hamas was not even mentioned in Joschka Fischer’s “Conceptual Paper”. This was by no means an accident: none of the 56 Middle East press releases published by the German Foreign Office between January 2001 and November 2003 contains a single reference to Hamas, Islamic Jihad or Hezbollah. The central message of the so-called “Fischer-Plan” was quite different: “Both parties (Israel and the Palestinians) are unable to resolve their conflict without outside help. Therefore what is needed is a Road Map and a timetable on how to achieve the Two-State Solution.” The German proposal contained the immediate proclamation and recognition of a Palestinian state whereas a final arrangement of crucial issues such as the question of Jerusalem or the final settlement of borders should be achieved within two years. In addition, it called for “a third party to supervise the procedure” as well as “an international security component.” Only this would be the “solution” announced the German Foreign Office: Two states, Israel and Palestine, “living in peace … side by side”.[iv] Really? If this was true, why then did Yasser Arafat leave the negotiation table at Camp David three years ago? Why then have the Palestinian leaders, during the last 60 years, torpedoed any opportunity of creating a Palestinian state next to a Jewish one?

“Next to” or “instead of”, Israel?

When for the first time Palestinians were offered their own state next to a tiny Jewish one in 1937, the Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin el-Husseini, refused to accept the offer. His anti-Zionist attitude was based on blatant antisemitism. He considered his goal in life to be thwarting the creation of any Jewish state. When the United Nations passed its Partition Resolution in 1947, there was a second opportunity for creating a Palestinian state. Again, Amin el-Husseini exercised his veto, and thereby triggered the Arab war against Israel’s existence. No Palestinian state was created between 1948 and 1967 when the West Bank belonged to Jordan and the Gaza Strip to Egypt. The next opportunity followed the 1967 war when Israel offered to return those territories in exchange for peace. “No peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel!”, was the answer from the Arab summit meeting in Khartoum on September 1, 1967. Finally, in 2000, Israel’s prime minister Ehud Barak offered the Palestinians the Gaza Strip and 97 per cent of the West Bank, including half of Jerusalem. Arafat refused and instigated the second Intifada. And today? With the whole world, including Israel, supporting the creation of a Palestinian state, it would be relatively easy to resolve the remaining disputes in a mutually agreeable fashion were this in fact the desired goal. However, the more hopefully the peace process began to develop in the spring of 2003, the more mercilessly the suicide attacks became, without the Palestinian Authority taking any steps to prevent them.

The result is clearly evident: The only two leaders the Palestinian movement has ever had, Amin el-Husseini and Yasser Arafat, never desired the creation of the 22nd Arab state next to Israel; they always wanted the only Jewish state to disappear from the face of the earth either immediately or step-by-step. Why else did Arafat treat the Oslo Peace Plan as being equivalent to the tactical cease fire (or hudna) of Muhammad in the year 628? Why else did he sing the praises of the “martyr’s death” as recently as June 1, 2003? Why else did he ensure that even the most recent school books show the whole of Israel as being Arab Palestine?[v]

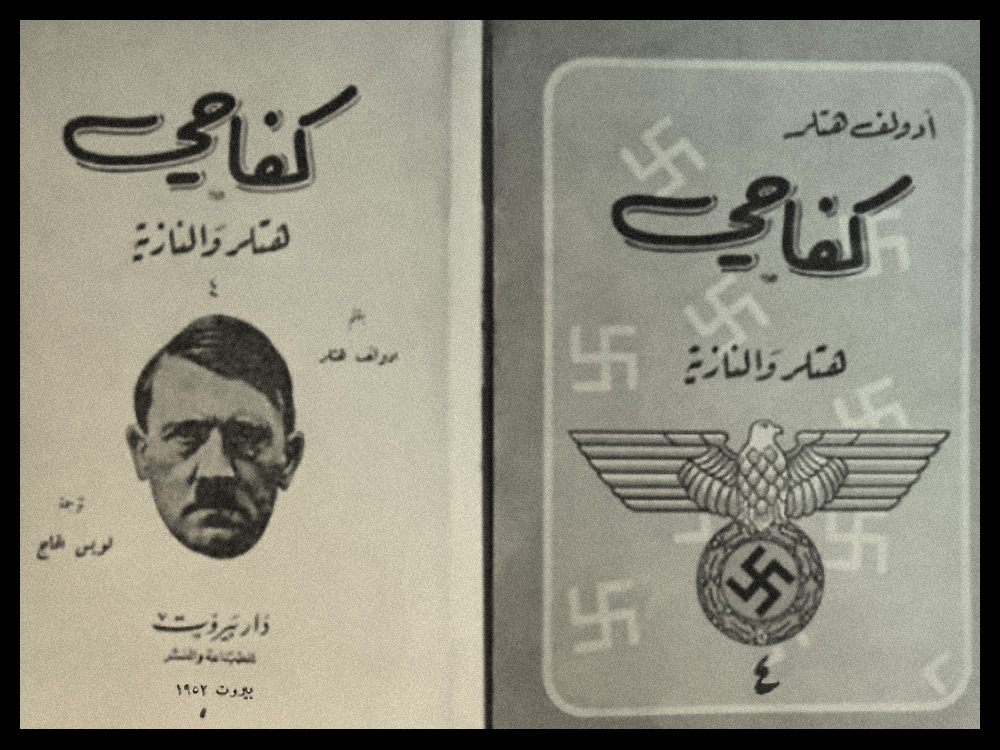

The eradication of Israel is openly and persistandly proclaimed by the influential Islamists of Hamas.[vi] In the Hamas’ weekly newspaper, their second most senior leader, Aziz al-Rantisi, recently “unmasked” the “myth of the gas chambers” with a clear reference to those who deny that the holocaust ever took place: Garaudy, Irving, Honsik and Toben. At the same time he puts the blame for World War II on the conspiracy of “Zionist banks”, thus integrating both of the ideological roots of Hamas: the denial of the shoah combined with the myth of a world-wide conspiracy of Jews.[vii]

It is just this demonization of Jews as being the eternal evil that makes the murdering of Israeli civilians look like acts of liberation, and that provides the phantom reason for Hamas’ ambition to destroy Israel. Obviously, this Nazi-like antisemitism which permeates the Charter of Hamas has nothing to do with a quarrel about occupied territories. The same is true with respect to the pathological longing for death which the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, Hassan al-Banna, already propagated in 1938 as the Islamist’s main guideline. [viii] Islamism allows Muslims to come closer to Israel’s Jews in one case only: with the aim of killing them. The more blood spilled in Palestine, whether Muslim or Jewish, the better the mood of Hamas.

It is true that religious fanatics are to be found in Israel, too, but the slogan “land for peace” has prevailed in Israel for decades, whereas a majority of the Palestinian elite either want “land without peace” or “peace without land”, but without Israel. [ix]

Perhaps a two-state solution will provide permanent normalisation in the long run, putting an end to economic misery and fear on both sides. Today, however, the real Palestinian supporters of a two-state solution represent a minority who are slandered as being “collaborators” and are left open to attack. That is why we have to consider the German proposal of April 2002 to establish a Palestinian state as soon as possible as being provocative. Up to now, the rapid proclamation and recognition of a Palestinian state would be tantamount to rewarding suicidal mass-murder. As long as Arafat and Hamas are in control, any Palestinian statehood will provide nothing but a sanctuary for jihadists. Against this background, how can we explain the creation of the Road Map Peace Plan and its support by the USA? Let us accept Joschka Fischer’s invitation. Let us take a closer look at what “the Europeans have achieved in the Middle East.”

Dissonant tones in the “Middle East Quartet”

From the outset, dissonant tones have characterized negotiations within the Middle East Quartet. For example, the German assessment of Islamism has always differed and continues to differs greatly from the US understanding. Of all countries, the German government has chosen to ignore what is all too familiar from Germany’s past: blatant antisemitism, such as that continuously expressed by Hamas. Consequently, the German foreign office does not classify Hamas and the Islamic Jihad as being combatants who are waging war on Israel. Instead, it has presented Islamistic suicide terror as a false though somewhat comprehensible response to an alleged dead-end street situation: ”It is not the violence of the second Intifada which has caused the failure of the peace process, it is rather the failed political process which has caused the violence.” [x]

Whereas the USA considers a cease fire to be the prerequisite for any peace agreement (and thus the destruction of the Islamist’s terrorist infrastructure to be the prerequisite for Palestinian statehood), Germany’s priority is quite the opposite. As Joschka Fischer claims: “Nothing but the prospect of a permanent peaceful solution will bring about a lasting truce.” [xi] In April 2002, when the Intifada reached its peak, Fischer even stated that “the Middle East crisis will either enforce its solution or escalate – that’s the alternative … That is why I prefer the speedy proclamation of the [Palestinian] state. Our French friends see it the same way.” [xii] This recipe, however, is bound to fail. You cannot contain terror by making concessions to the terrorists.

Germany’s nonchalant attitude towards the anti-Jewish suicide attacks has corresponded with its forceful support of Arafat. After the SPD/Green government came into power in September 1998, Germany became the most important supplier of funds to the Palestinian Authority. Since the beginning of the Al-Aqsa-Intifada in September 2000, the political significance of this financial support has grown. Germany, however, has not used its influence in order to bring about new negotiations and peace in the area. Instead, PLO-commander Yasser Arafat was given the green light when Chancellor Gerhard Schröder paid him a visit in November 2000. At that time, members of the Chancellor’s delegation pointed out that “Schröder did not want to put pressure on Arafat in order to get him back to the negotiating table. It did not make sense to connect foreign aid to the willingness of the Palestinians to compromise.” [xiii] It is sad to note that since then the increase in Germany’s financial support for Arafat has corresponded to an increase in suicide attacks.

In addition, Yasser Arafat enjoys Germany’s diplomatic support. As early as February 2002, Arafat was isolated. Israel had broken off all contact with him. The USA publicly blamed him as being the most responsible for the escalation of violence in the Middle East. Arafat was even isolated within the Arab world because of his latest rapprochement towards Iran. Such was the situation when Joschka Fischer put an end to Arafat’s isolation. “Arafat’s enthusiastic ‘Thank you! Thank you! Thank you!’ for the visit of the German foreign minister sounds much like the Palestinian leader’s triumph over Israeli tanks positioned at his front door”, reported the German daily, Die Frankfurter Allgemeine, in February 2002. “Fischer as well as the European Union did everything possible in order to initiate Arafat’s resurrection. .... As long as Israelis are being terrorised, and as long as Arafat passively if not actively holds his protective hands over the perpetrators of such terror, then it would be very difficult for anyone to recommend this isolated Palestinian president as being a partner in negotiations. But Joschka Fischer did exactly that.” [xiv]

Of necessity, such contrasting opinions about Arafat and Hamas produce differing opinions about Israel’s policy of defense against Islamism as well.

While the USA acknowledges Israel’s right to defend herself against terror, Germany takes a seemingly neutral stance by talking about a “spiral of violence”: Israel’s government is placed on a par with Arafat with both sides being termed irresponsible and “no longer capable of solving the conflict”. Joschka Fischer put it this way in English: “There was an agreement – say, hello. The interpretation of the one side is ‘good night,’ of the other side is ’good morning,’ so this leads to nowhere. Therefore, you need a vital third party for the implementation (of the Road Map).” [xv]

Dispute over Arafat

As mentioned earlier, the Road Map’s diplomacy was characterized by transatlantic conflicts from the very beginning. President George Bush, however, who faced “increasingly pointed demands from the Europeans and moderate Arab States for progress in resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict” eventually accepted “crucial points of the German conceptual paper,” as the homepage of the German Foreign Office emphasized. [xvi] In his second Middle East statement on June 24, 2002, the American President adopted the concept of rapidly proclaiming a provisional Palestinian state by announcing that a conclusive arrangement might be reached within a three-year period. He did so with the reservation that, beforehand, a new Palestinian leadership without Arafat that fights terrorism and destroys the terrorists’ infrastructure would have to be established.[xvii]

But just a few days after Bush had issued his statement, Joschka Fischer distributed a second paper to the Middle East Quartet, focussing on the attempt to retrieve Arafat’s honor. According to this paper, Arafat should not be forced to resign but instead he should “call into being a transitional government with a prime

minister.” [xviii] This proposal had little in common with the American prerequisite “to elect new Palestinian leaders not compromised by terror”. It was unlikely that a prime minister would remove from office that person of all people to whom he owed his new post.

Accordingly, when in July 2002 the Quartet convened in New York City, the different opinions on how to proceed were polarised. Here was the USA appealing to the Europeans to stop sending Yasser Arafat direct payments of 10 Million dollars a month in order to force real policy changes to take place. Over there were the Europeans, supported by the UN and Russia, insisting on Arafat as the legitimate Palestinian leader.[xix] However, in arguing about Arafat, the overall orientation towards the Middle East crisis was at stake: “pro-Arafat” would mean being in agreement with the second Intifada and the vision of a Palestinian state created by means of Islamist terror; “contra-Arafat” would mean striving for a new beginning with a Palestinian state opposed to Islamist terror and in favor of normal relations with Israel, thus securing long-lasting peace.

Actually, in the course of this summer’s meeting, the Quartet should have broken apart because the Road Map turned out to be a map with its signposts pointed in different directions. But again the United States patched up the quarrel by accepting Joschka Fischer’s idea of having a new prime minister installed by Yasser Arafat. Was it that the US Government made this compromise because of the looming transatlantic disagreements concerning the war on Iraq?

At the end of August 2002, the foreign ministers of the European Union approved the so-called EU-Road Map “which was basically oriented towards the German government paper”, as the homepage of the German Foreign Office proclaims. “The European Union adopted the three-stage plan covering the period 2002-2005 and including all important details as well as the prime minister idea.” In September 2002, this European version of the Road Map was transformed into the joint Middle East Quartet Road Map. In December 2002, the final wording of the peace plan was adopted at the Quartet’s meeting in Washington and was presented to the Israelis and the Palestinians on April 30, 2003. What was it all about? Period I (“up to May 2003”): Israel is to withdraw to her previous positions of September 28, 2000, and is to remove all those settlements created later than March 2001. The Palestinians are to centralize their security apparatus, and to initiate steps in order to “destroy the terrorist infrastructure” through efficient operations , whereas the Arab states are to stop “any kind of public or private funding” for groups supporting violence and terror.

Period II (“June 2003 until December 2003”) is supposed to take place after the prerequisites of Period I are met. At the end of the second period “an independent Palestinian state with provisional borders and attributes of sovereignty” is to be founded and recognised by the United Nations, if possible. Period III (“2004-2005”): Negotiations concerning a complete and conclusive agreement for the Israel-Palestine conflict should take place at this time only.[xx]

Sabotage at Ramallah

As soon as the valid period of the Peace Plan began, the former differences intensified. Arafat humiliated his new prime minister, Mahmud Abbas, and insulted him by calling him a “traitor”. From the outset, he thwarted the Road Map peace plan by keeping two-thirds of the security forces under his control as well as by giving his tactical support to the suicide attacks of the Fatah-related Al-Aqsa Brigades. Nevertheless, Arafat was backed further by Germany and the EU in spite of increasingly harsh criticism from Washington. [xxi]

Hamas even called the Road Map a “Zionist conspiracy” and embarked on a new series of suicide attacks in order to further destroy the peace process. In spite of this, on July 3, 2003, the European Council refused to put Hamas on its “black list” of terror organisations, or to freeze its bank accounts. The speaker of the EU commission, Reijo Kempinnen, went so far as to say that Hamas was a “legitimate” organisation because of its activities in welfare work. He stated: “You can’t say that the whole of Hamas is a terrorist organisation, and certainly that is not our position.” [xxii]

Contrary to the provisions of the Road Map, Joschka Fischer tried to integrate Hamas permanently into the peace process. In June 2003, at a press conference in Cairo, he made the demand that “a ‘permanent agreement for a cease-fire’ would have to be achieved with the Islamist Hamas movement and other groups.” A US government official was quoted the next day in the New York Times saying: “How can a group determined to wipe Israel off the face of the earth become a partner in the peace process?” Fischer’s reply to this statement is unknown. [xxiii]

A debate on how do deal with Hamas arose within the EU after August 19, 2003, when a Hamas suicide bomber got on to an overloaded Jerusalem bus and killed 23 passengers. At the beginning of September, according to a report on EUobserver.com, “the UK, the Netherlands and Italy are all in favour of blacklisting the group but will face tough opposition from France and Germany who are keen to stress the importance of the political wing’s humanitarian projects to people on the ground.” [xxiv] The Europeans changed their course only after the peace plan was shattered. Hamas was added to the “black list” on September 6, 2003 – the very day Mahmud Abbas resigned. While this political decision turned out to be a major accomplishment, it needs to be emphazised that this ban does not include offshoots of Hamas allegedly engaged in social welfare. [xxv] .

Thus we have to conclude that Germany and the EU by ignoring the warnings and appeals from Washington not only weakened the peace process but made themselves contributors to the failure of Palestinian’s new prime minister, Mahmud Abbas.

Didn’t the Germans and the Europeans in fact sabotage their own efforts by following this policy? Not at all – they simply continued to do what they had done all along, thus shattering the intentions of the USA such as replacing Arafat, stabilizing the government of Mahmud Abbas, weakening and eventually crushing the Islamists, compelling Israel’s retreat from the occupied territory, creating regional stability. But what could be the German government’s intentions? Some clues are given in the programmatic report “Framework of a German Middle East Policy”, published in August 2001, which was written jointly by Middle East experts from Germany’s Conservative Party, the Social Democrats, and the Greens. [xxvi]

This report takes for granted that there is a special relationship between the Germans and the Palestinians: “Supporting the creation of a Palestinian state is a priority. Financial aid for Palestinians exceeds financial aid given to any other single nation. This aid is the German government’s deliberate and direct decision. Germany should not shirk its duty as a midwife and godfather of the future Palestinian state.”

“Godfather of Palestinians”! Why should Germans of all people want to be the Palestinians’ godfather? Is it that they want to make good to the Palestinians their previously wrongs to the Jews? And if a godfather, why of all people that of the Palestinians? Is it because they believe they know what it is like to be “misused” by Jews? It is obvious that the Middle East will always remain a minefield in terms of social psychology in Germany. Unconsciously, so it seems, the after-effects of the Shoah are having an influence on German policy as well as on the German discourse about Israel and the Palestinians.

But what about “priority Palestine” if the Islamist’s terror continually blocks the path to Palestinian statehood? This case is anticipated in the German “framework”-document, as well. “Germany has to make it clear that it recognizes the mainly Arab character of the Middle East and that her relationship towards the Arab world is not at all dependent on the success of the Middle East’s peace process.” This ranking is beyond doubt: Relations towards the Arab world are not subordinate to the success of the efforts to create peace in the Middle East. However, the peace solution in conjunction with Israel’s security is secondary to Germany’s good relations with the Arab regimes. Quite often, however, these regimes have their own reasons for being interested in the continuation of the conflict between Palestinians and Israel. “Priority Palestine” and – even more important! – “Priority Arab world”: These priorities have determined German Road Map policy up to now. Yet another point has to be added. It’s true that Germany could expand and strengthen its relationship towards the Arab world as an influential partner and side by side with the United States. At the time being, however, the logic of German foreign policy takes for granted fierce competition with the USA over influence and power, especially in the Middle East.

Alliance against America

Only four months after Joschka Fischer’s boasting in May 2003 about “what we Europeans have achieved in the Middle East”, it was replaced by almost conspicuous restraint. In Germany’s media, the government’s obvious share in responsibility for the Road Map’s debacle has been swept under the carpet. In the treasured tradition of “fingerpointing” the USA and Israel were being held responsible for its failure. Consequently, the talk was suddenly about a “Peace Plan formulated by the Americans” which “in its simplicity was inspired by typical American wishful thinking”. Or as a Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung columnist gloatingly wrote: “Did the Israelis and the Americans really believe that this plan would succeed?” The USA might have “overtaxed herself”. [xxvii]

There are some people within the European Union who might be happy about any US setback. Already in 1998, the director of the German Orient Institute, Udo Steinbach, explained that “many in the Middle East consider Germany to be the great power of the future” which “is capable of forming a counterweight against an all too dominant American exercise of power.” He went into raptures when mentioning the “expressions of support” which “Germany traditionally enjoys within the whole region.” There is no doubt, however, what “tradition” in this respect means.

It appears that the 9/11 attacks as well as the war with Iraq have further strengthened Germany’s desire to become an important alternative to the USA within the Arab/Islamic world. This is why Germany is striving for good relations with Islamists.

This orientation was recommended in a study presented by the influential German Bertelsmann-Foundation to a high-ranking Middle East conference which took place in Kronberg, Germany, in January 2002.

According to this study, ”the EU should not devote its time on the futile search for an internationally accepted definition of terrorism especially in the Mediterranean context, where, in the public discourse, the lines between terrorists, resistance fighters and opposition groups are blurred.” Isn’t this reference to the “public discourse in the Mediterranean context” a flimsy cover for tolerating groups such as Hamas by blurring the lines between terrorists and opposition groups in a European policy context as well? What does this study recommend instead? “It is of the utmost importance”, it states, “to start a frank cultural dialogue with the Southern Mediterranean countries to discuss mutual concerns…. Moderate Islamists should be included in this dialogue.”[xxviii]

Germany’s government seems to have adhered to these recommendations. It wants to continue co-operation with Islamists instead of isolating them. In that respect, its consideration for Arafat and Hamas may have served as a signal to the Arab/Islamic world. Isn’t this signal, however, tantamount to the encouragement of Jihadism against Israel? Why should the Arab world join the American efforts to isolate and fight Hamas or other Islamist terror groups more seriously if Germany and the EU decline to do so?

Economic factors are complementary to this policy. Saudi-Arabia, for example, is not only the most important financial backer of Hamas, it is also Germany’s most important trading partner within the region. Iran, ruled by Islamists, is not only the founder and the financial backer of Hisbollah and the Islamic jihad but it is Germany’s export business eldorado. In 2002, German exports to Iran increased by 25 %; in 2003 by a further 23 %! Between 2001 and 2002 Germany’s mechanical engineering exports to the Middle East increased by a record-breaking 24.2 %.[xxix]

Germany’s orientation towards these most reactionary Arab regimes not only disregards Israel’s interests but Palestinian interests as well. At the beginning of July, 2003, some 56% of the Palestinians proved to be in favour of the peace plan. [xxx] Nevertheless, Germany translated “priority Palestine” into “priority Arafat and Hamas”. Not one member of the German government has critizised the disastrous consequences of the second Intifada as pointedly as did Mahmud Abbas. In October 2002, when he was the PLO’s Executive Secretary, Mahmud Abbas, explained: “What happened in the past two years, as we see today, is the complete destruction of everything we built [under Oslo], and what we built before. … The militarization of the Intifada was a complete mistake.” [xxxi]

A mistake for the Palestinians, an advantage, however, for others. Why did the United States consider it to be necessary to share to some extent with Germany and the EU its responsibility for the Middle East? “The most compelling factor of influence is the development of the situation and its potential to escalate”, stated Joschka Fischer. [xxxii]Yes indeed! It was only the series of terrorist attacks in Bagdad that compelled the United States to permit the influence of the United Nations and the EU in Iraq to grow. It was only the suicidal terror of Hamas that compelled the USA to accept the Middle East Quartet and the European Union’s growing influence with respect to Middle Eastern affairs.

This is the reason why we have to answer in the affirmative the following delicate question submitted by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung’s editoral: “Could it be that countries which are self-confident in regards to power politics might possibly be interested in seeing that the United States’ success in fighting terrorism turns out to be neither triumphant nor definite? “[xxxiii] Isn’t that exactly the issue at stake? Any foreign policy success of the USA seems to be to the detriment of the EU. The less success the United States has, however, the greater is the opportunity for Germany and the EU to present themselves as an alternative to the Bush administration and to profit from its failure.

Thus, the transatlantic disputes about the Road Map shed light on the development of contradictions concerning the struggle against Islamistic terror in general. Whereas Israel and the USA have declared war on Islamism and antisemitism in a fashion at least, Germany and other European powers are more or less currying favor with, and are trying to use, those movements to their own advantage.

“Just look at what we Europeans have achieved in the Middle East!” Joschka Fischer bragged on May 8, 2002 to the German weekly Die Zeit. Later in this interview, Mr. Fischer was to define what he would consider to be “the specific European” in world affairs. Here is his answer: “The difference is whether there will be a co-operative perspective towards the Arab-Islamic crisis belt or a hostile one.” The “achievement” of the Europeans with regard to the Road Map demonstrates what this answer might imply: More co-operation with Saudi-Arabia which is financing Hamas, more co-operation with Teheran and its followers in Ramallah and Jenin, more co-operation with the patron of terror, Yassir Arafat?

Dr. Matthias Küntzel, a political scientist and author, lives in Hamburg, Germany. His new book “Djihad und Judenhass. Über den neuen antijüdischen Krieg”, was published in 2002. (Ca ira-pubs., Freiburg, Germany, 180 pages, € 13.50) You will find Küntzel’s paper „Islamic Antisemitism And Its Nazi Roots” which was partly presented in his Keynote Address at the conference on “Genocide and Terrorism – Probing the Mind of the Perpetrator” in April 2003 at Yale University, New Haven, on:

Statement on the occasion of a discussion on Islamist antisemitism organized by the London Centre for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism at King's College London on November 3, 2025 London, November 3, 2025 About the book "Hamas-The Quest for Power" by Hamas experts Beverley Milton-Edwards and Stephen Farrell Hamburg, October 30, 2025 Lecture from March 31, 2025 on the occasion of the Contemporary Antisemitism Conference in London London, March 31 2025 Are there lines of continuity linking the anti-Jewish terror of the Nazis with that of Hamas? Indiana University, Institute For The Study Of Contemporary Antisemitism: Research Paper 2024-5, November 2024 The months following the massacre have revealed the failure of previous Western Holocaust education, which has never wanted to know anything about the after-effects of Nazi ideology in the Muslim world. Hamburg, August 7, 2024 I delivered this speech on June 4, 2023 on the occasion of the Klangteppich V - Festival for Music of the Iranian Diaspora in Berlin Hamburg, 04.07.2023 An introduction to some discoveries and arguments of my new book: “Nazis, Islamic Antisemitism and the Middle East: The 1948 Arab War against Israel and the Aftershocks of World War II”. FATHOM, JUNE 2023 Contribution to the conference “Lessons and Legacies XVI – The Holocaust: Rethinking Paradigms in Research and Representation” on November 12–15, 2022 in Ottawa Ottawa, November 13, 2022 This is the speech I gave on November 17, 2022 in Gainesville, University of Florida University of Florida, November 17, 2022Recent articles:

The religious dimension of October 7

Propaganda for the educated

Hunting Jews: The radicalization of antisemitism since October 7

October 7th and the Shoah

The Denial of Continuity: October 7 and the Shoah

Broadcasting as a weapon: The Persian-language Nazi propaganda and its consequences

The 1948 Arab war against Israel: An aftershock of World War II?

The Lasting Impact of Nazi Germany's antisemitic propaganda in the Middle East 1945-1948

The Iranian Uprising and the Nuclear Threat: How Should the West Respond